This blog post was written by library volunteer Diane Leone.

Any resident of Scotia or the surrounding area is familiar with Collins Park, a recreational gem visible to anyone approaching the village of Scotia from the Western Gateway Bridge. Having served the community for approximately one hundred years, the park’s origins are inextricably linked to the founding of Scotia itself.

One of the founding fathers of the village of Scotia was Alexander Lindsay Glen (called by the Dutch Sander Leendertse Glen), from the Scottish noble house of Lindsay. According to his descendants, in 1655 he purchased 100 acres of land from the Mohawks, members of the Iroquois confederacy. Lindsay was also one of the original fifteen men who held land from the Schenectady patent of 1664. The house he built, which he called Nova Scotia in honor of his homeland, was unfortunately too close to the river’s edge, with erosion weakening the foundation. As a result his son, Johannes, built what is now called the Glen Sanders Mansion in 1713. Upon his death, his son Jacob inherited the home with the proviso that he construct a house for his brother Abraham. That structure, the Abraham Glen House, currently houses the Scotia branch of the Schenectady Public Library.

In 1842 Theodore Sanders, a descendant of Jacob’s daughter Deborah and husband John Sanders (who consolidated all of the family’s holdings in the Sanders name), sold the Abraham Glen property, including the home and 78 acres, for $11,925 to two brothers from Ireland, James and Charles Collins. The land included what was first called Glen Lake, then Sanders Lake, and later named Collins Lake, where the brothers ran an ice business, cutting ice from the lake and distributing it in a wagon advertising “Collins Ice.”

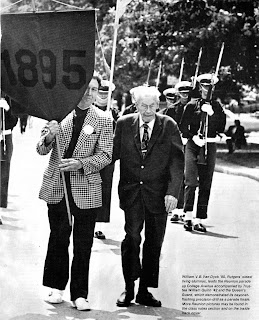

In

1895 the brothers created a private park that sported trees for shade, as well

as seating, a baseball diamond with bleachers, tennis courts, and a pavilion

for dancing. The park offered recreational activities in summer, as well as

winter. The J. C. baseball team, named for James Collins, played at the park.

Visitors also enjoyed the lake, where they could rent flat-bottomed boats from the lake house for 10 cents an hour, and also pick pond lilies for 2 cents per lily. The winter offered tobogganing, a wildly popular sport in the latter part of the 1800s. The photo below, from the 1870s, shows the toboggan slide, which ran north from Dyke Road, now Schonowee Avenue.

The background to the creation of Collins Park is not entirely clear. The private park closed in 1905 after James Collins’s death. In 1922, with the death of his daughter Anne, the Abraham Glen home was bequeathed to the Daughters of Wisdom nuns, who ran a children’s home. Since the house did not meet their needs, Anne Collins’s executors offered the land to the village, which acquired the Abraham Glen house—it became the Scotia Free Library in 1929— and the attached land, including the western rim of the lake, for $30,000, with the proviso that the land be designated a public park named after the Collins family. Fund-raising activities helped defray the cost, $5,000 of which was donated by General Electric. In 1924, Collins Memorial Park consisted of 26 acres maintained by the Collins Park board. That board handed the park over to the village in April of 1928, with Scotia now responsible for completing the payment for the property. The deed was executed that July.The rest of what came to be Collins Park was acquired separately. A man named Neil Ryan owned property to the east of the park, including the remainder to the lake. His proposal to sell the land to the village for $65,000 came before the village board in November of 1928. Unfortunately, no further documentation is available on the actual vote, or how that section of land was incorporated into the park. Interestingly, the deed for that section of the park is dated 1937, with a different seller.

Thus was born Collins Memorial Park. It provided a variety of activities, including tennis, baseball, horseshoes, swings, toboggan slides, and skating equipment for children, as well as individuals to oversee the playground.

In Scotia 100 Years...Memories of a Village, lifetime resident Marion Gilgore recalls the warning system for ice-skaters on Collins Lake.

“There was a building right behind the library with a flagpole. If the flag was blue—the ice was safe and if the flag was red—the ice was too thin to skate on. Of course there was always someone who would try to skate when the flag was red and fall through the ice. Then they would call the fire department."

After World War II, the state undertook a project to deepen the Erie Canal network and needed a site to deposit the excess dredging material. Scotia mayor, Bill Turnbull, made an arrangement with the State Waterways Maintenance Department to have this material fill in the lower part of Collins Park, thus expanding it. In 1946 more than 1 million cubic yards of fill was added to a marsh area currently inside the park and on the side of Schonowee Avenue abutting the Mohawk River. The community—both individuals and groups—assisted with donations of trees, as well as the creation of a Little League park and beach area and the construction of additional tennis courts.

Around the same time, the now famous Jumpin’ Jacks had its start. Jack Brennan purchased land along Schonowee Avenue from the Sanders family to build what was initially called Twin Freeze, and then Jumpin’ Jacks, where he would sell soft ice-cream, a newly popular treat.

Over the years, facilities have been added or improved, thanks to service organizations such as the Kiwanis Club (which funded the Kiddies Park) and the Rotary Club. In the 1960s, the swimming area and beach were moved to the current area. The park was a popular venue for baseball, basketball and even Scotia-Glenville High School football games. As Alan Hart so fondly reminisces about the Tartans in Dear Old Scotia:

Before the new field behind the school was laid out, however, I remember going to home football games on the old field at Collins Park in the 1950s. It was a blast! The field was laid out east to west in the bowl behind the library, and if you were a kid like I was, it was pretty easy to sneak in and watch the game without paying. The entrance was sectioned off with ropes, but if you waited for an opportune moment once the game had begun, you could duck under the ropes when the man tending the entrance was watching the action on the field. Then you could use that money your mother gave you for your ticket on an extra hotdog or two! (2)

A wonderful recreational area on the river side of Schonowee Avenue next to Jumpin’ Jacks is Freedom Park, which was created in 1976 as part of the state’s Bicentennial celebration. It has picnic tables, an amphitheater/stage area where free summer concerts draw large crowds, and a small dock called Scotia Landing. Quinlan Park is a popular fishing area located on Washington Avenue on the eastern edge of Collins Lake.

The lake is a 55 acre oval-shaped body of water located in the park’s center. Residents use it for fishing, ice-fishing and boating. Unfortunately, the lake is filled with invasive aquatic species, such as water chestnuts, milfoil and pondweed. To remedy this situation, dredging was performed in 1977-78 and again between 1988 and 1992, when the unearthing of Native American artifacts forced the town to stop. To make matters worse, the 2011 tropical storms Irene and Lee deposited river sediment into the lake, closing this popular spot for swimming. In June of 2021, the town of Glenville put into effect a plan to eliminate milfoil. It is hoped a water herbicide treatment in the spring of 2022 and 2023 will help rid the lake of water chestnuts.

Some interesting stories are associated with Collins Lake. On November 20, 1857 a local newspaper reported the strange tale of a sea serpent spotted by broom corn workers as well as two other men. This frightening beast was described as “a most hideous monster; it was variously reported to be from seven yards to a half mile long and was said, when in an angry mood, to lash the waves with a gigantic tail until the lake was one sheet of foam.” Its actual appearance, when caught, did not quite live up to expectations. It was said to be on display at Schenectady’s Anthony Hall. The creature apparently put in another appearance on March 28, 1934, as reported by Scotia resident Dr.Wilber D. Rose in a rather sardonic tale printed in Scotia, 100 years 1904-2004: Memories of a Village. The “monster” was said to be displayed in the State Education Building. The reader will have to decide on the veracity of these stories.Another incident in the lake’s history occurred in 1948, when four boys borrowed a rowboat without permission and proceeded to the island in Collins Lake. The quite irritated owner swam to the island to recover his craft, leaving the culprits stranded. In the afternoon, the father of one of the boys saw the quartet on the island, gesturing and shouting. Recognizing his son, he went to the police station, where the boat owner was persuaded, rather reluctantly, to rescue the group.

Today, Collins Park continues to draw the community throughout the year. In winter, families enjoy sledding down the hill behind the library (the former Abraham Glen House), and hardy souls can be seen ice fishing on the frozen lake. During the warmer months the park comes alive with a variety of activities. The tennis courts are popular, and there is always at least one baseball game going on, with friends and families rooting for their teams and players. Walkers and joggers fill the park paths, and picnickers at Freedom Park enjoy the waterfront view. People flow between the park and Jumpin’ Jacks, where they can grab a quick bite or maybe a refreshing ice cream. On certain summer evenings, people bring lawn chairs to enjoy the musical entertainment in Freedom Park’s amphitheater. In July and August the US Water Ski team holds daily practices and weekly performances along the Mohawk shore, where large, enthusiastic onlookers crowd the shoreline behind the restaurant and in Freedom Park.

The Collins family left the village of Scotia a wonderful legacy.

Special thanks to Village of Scotia historian Beverly Clark for her help in locating and gathering information for this blog.

Bibliography:

Armstrong, Shirley. "Boys 'Marooned' 4 Hours on Collins Lake Island." Schenectady Gazette, June 26, 1948, 6.

Briere, Shenandoah. "Village of Scotia Weeding out Collins Lake." Daily Gazette (Schenectady, NY), August 8, 2021, 15.

Campbell, Ned. "Familiar Summer Story: Collins Lake Beach Closed." Daily Gazette (Schenectady, NY), June 5, 2014, A1.

Hart, Alan. Dear Old Scotia. Scotia, NY: Old Dorp Books, 2004.

Hart, Larry. "'Deal Struck 51 Years Ago Influenced Park's Growth." The Gazette (Schenectady, NY), September 7, 1997, B07.

Schenectady County Historical Society. Glenville. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2005. Scotia, 100 years 1904-2004 : Memories of a Village. N.p., 2004.

"Settlers at Schenectady, 1661-4." In History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614- 1925, edited by Nelson Greene. Chicago: S. J. Clarke, 1925.

Sloan, Frances Anderson. "History Walks with Scotians" columns in the Scotia-Glenville Journal.

Weatherwax, Bonnie, Heritage Coordinator. Scotia-Glenville American Revolution Bicentennial Book of Remembrances, June 18-26. 1976. N.p., 1976.

Collins Park clippings files at the Schenectady County Historical Society