Saturday, December 27, 2014

A Young Man's Mathematics Lessons

This blog entry is written by Schenectady County Historical Society trustee John Gearing.

Among the manuscript treasures of the Grems-Doolittle Library lies an oft-overlooked gem: the Glen-Sanders Papers. Members of the Glen and Sanders families resided in Scotia's eponymous mansion for over 200 years. In the mid-twentieth century the estate was broken up and the remaining Glen-Sanders papers came into the possession of the New-York Historical Society. The Schenectady County Historical Society has a copy of the papers on eighteen reels of microfilm. The collection includes correspondence and notes (the earliest of which is dated 1674), account books, maps, wills, and genealogical records.

A careful reading of such papers can help us better understand what life was like in Schenectady in earlier times. While one could be excused for assuming that eighteenth century life was far simpler and much less sophisticated than it is today, a mathematics lesson book in the Glen-Sanders papers suggests otherwise. The book bears the name of Daniel Toll and is dated 1790. The mathematics taught were practical in nature and covered topics essential to every successful merchant.

The first exercise taught young Mr. Toll how to subtract the weight of a container, the “tare,” to determine the weight its contents. For example, flour was sold at the wholesale level in barrels. This sounds simple, but some goods were sold in units of “hundredweights” (or 112 pounds) and tare was sometimes set at a percentage of the whole rather than the actual weight of the container. Conversions were often necessary. Also covered was the calculation of “Brokage,” which Toll defined as “the percentage charge levied by those called Brokers who find customers and selling them the goods of other men whether strangers or natives.” A budding merchant needed to calculate “tret” as well. Tret was the amount (typically 4 pounds per hundredweight) allowed for the wastage of goods during shipment.

Both simple and compound interest were covered in Daniel Toll's subjects. He was taught how to compute interest when the percentage was not a whole number, and how to compute either the return, the term, the principal, or the percentage when the other three factors were given. Fractions, both “vulgar” and decimal, were covered, along with multiplication.

The lessons were taught using pounds, shillings, and pence. Instead of being a decimal system like today's dollar, this system was based on multiples of twelve. Twenty pennies made one shilling, and twelve shillings made a pound. Merchants' calculations required converting pounds to shillings and pence, and vice versa. Some problems required converting everything to pence, completing the calculation in pence, and then reconverting the answer to pounds, shillings and pence.

Complex computations were taught using a sort of algorithm. For example, to determine the present value of a amount due to be paid in the future, Toll wrote:

“Answer

1. As 12 months are to the rate percent

So is the time proposed to a fourth number

2. Add that fourth number to ₤100

3. As that sum is to the fourth number

So is the given sum to the rebate

4. Subtract the rebate from the given sum

and the remainder is the present worth.”

Although this “answer” may be mystifying to modern eyes, a careful perusal of the Toll's sample problem shows that four steps above were easily translated into arithmetical calculations by students of the day.

Assuming the dates (1790 and 1793) in the lesson book are accurate, Daniel Toll would have been between 14 and 17 years old when learning the practical mathematics shown in this lesson book. The difficulty and complexity of Toll's math curriculum seems to compare favorably to that of today's students of the same age, suggesting that Schenectadians 224 years ago were not all that much different, in some respects, than we are today. Assuming that Jonathan Pearson's information is correct in his Genealogies of the Descendants of the First Settlers of Schenectady, Daniel Toll, it seems, grew up to be a physician, and not a merchant after all.

Thursday, December 18, 2014

Christmas and the Erie Canal in Schenectady

Larry Hart wrote in his "Tales of Old Dorp" newspaper column in 1980 that local resident Lew McCue, who grew up in Schenectady and worked on the canal in his younger days, "had a canal story or poem for almost any occasion." Christmas was no exception. McCue shared with Hart his memories of Christmas days during the canal era.

McCue shared his memories of his 1880s boyhood in Schenectady; he credited the canal with making the Christmas season brighter. Special and exotic goods arrived in Schenectady, brought to town by shippers operating on the canal, right before the November closing of the canal each winter. These shipments made fruits such as bananas, oranges, figs, grapefruits, and pineapples plentiful during the holiday season. The canal barges also brought wine, cheeses, nuts, ginger, molasses, books, hardware, cloth, and stationery from faraway places. While everyone appreciated these special goods flowing into town just in time for the holidays, McCue noted that those who remembered life in Schenectady before the canal opened in 1825 were especially awed by the range of goods that the canal made it possible to be brought into town.

The canal also offered a special holiday delight in the form of recreation. On the weekends just before Christmas, McCue remembered, Schenectady's merchants provided funds to have Japanese lanterns hung along the ice skating area of the canal (the area just south of State Street on what is now Erie Boulevard), and hired bands to perform music for the skaters. Wintertime horse races were also held along a mile length of the canal from the Washington Avenue bridge westward.

While local kids used the canal for ice skating, they also imagined that the canal provided a means for Santa Claus to hasten his travels across New York State. McCue shared with Hart that the children in Schenectady in the late 1800s believed that, rather than traveling with flying reindeer in the sky, Santa Claus' reindeer drew his sled along the frozen canal.

While a youth working on the canal, McCue also learned a holiday song from other canal workers, the lyrics of which he passed along to Larry Hart, who published them in his "Tales of Old Dorp" column:

There was always a Santa Claus on the Erie Canal,

Mrs. Claus powdered her nose and joined in as well.

There were cargoes of spice, nuts and logwood for toys,

And many other things for girls and boys,

And tons and tons of molasses, with a Christmas smell.

Yes, there was always a Santa Claus on the Erie Canal.

Friday, December 12, 2014

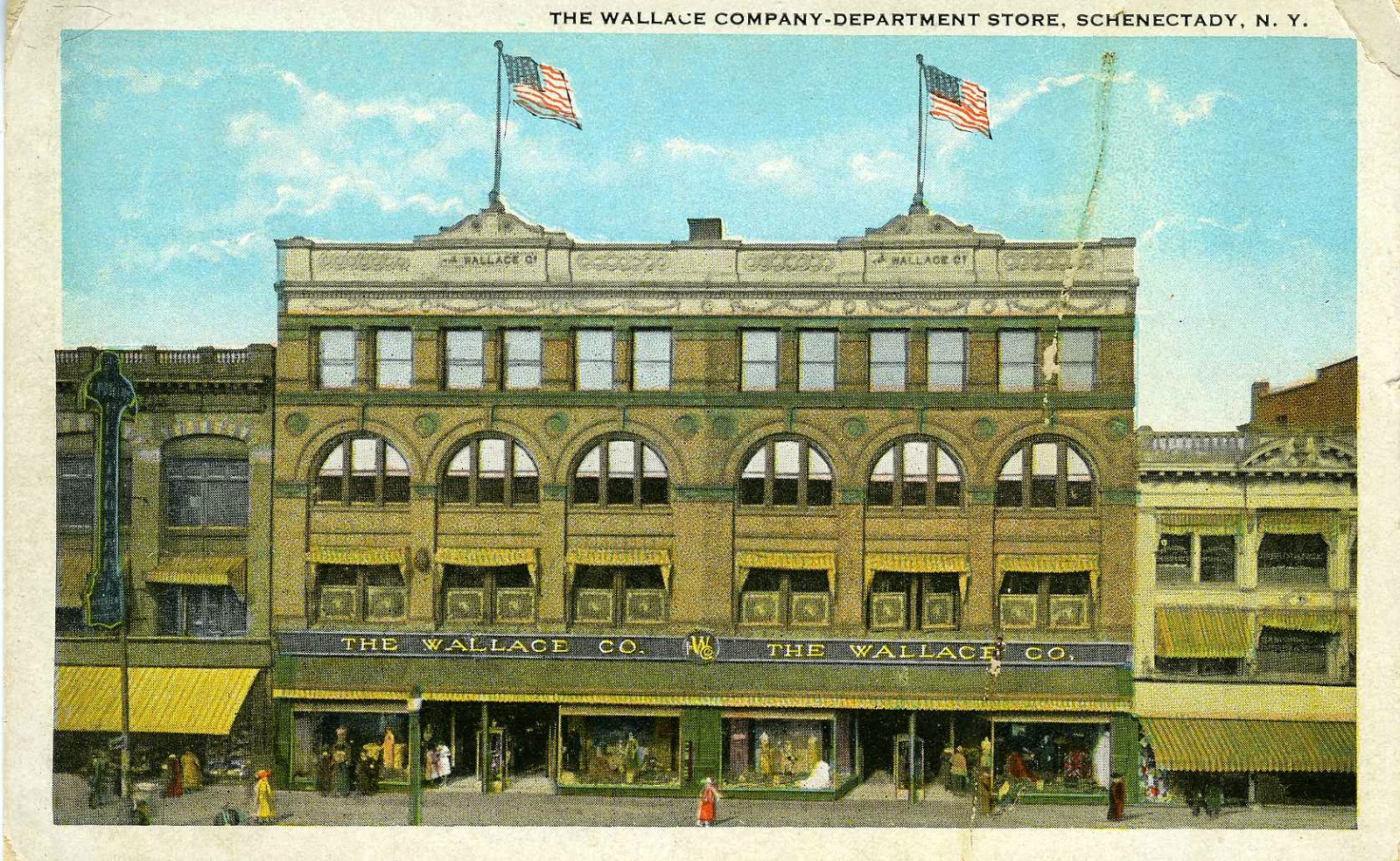

"The Shopping Center of the Mohawk Valley": Wallace's Department Store

This blog entry is written by Library Volunteer Ann Eignor.

Wallace's Department Store, a landmark at 413-417 State Street for many years, began as William McManus Dry Goods. The dry goods store first opened at 39 Ferry Street in 1822. It prospered and moved to what was then 101 State Street. In 1840, the McManus Building, constructed in brick, was erected at 137-143 State Street. At the time, it was considered one of the finest buildings in Schenectady; the building was razed in 1951 to make way for Schenectady Savings and Loan.

|

| Taken circa 1919, this photo shows the Wallace Company store after the 1911 expansion which doubled its size. Image from the Grems-Doolittle Library Photograph Collection. |

1875 saw the William T. McManus store sold to a group of partners led by Thomas H. Reeves. Among the partners were E.W. Veeder, Charles F. Veeder, and Charles Luffman. From 1875 until 1909 the store was known by various names -- T.H. Reeves, Reeves-Luffman, and Reeves-Veeder. Charles Veeder was responsible for moving the store "uptown" to 417 State Street. This was then the first large business to be located east of the railroad tracks, which were then at street level.

The Wallace name first appears in 1909 when the store was purchased by Andrew Wallace of Springfield, Massachusetts. It then became part of Consolidated Dry Goods, which owned department stores in several cities in New York and Massachusetts. Under the new owners, the the store doubled in size. The house next door, once the residence of the former mayor T. Low Barhydt, was demolished. In its stead a building arose with a facade that duplicated that of the existing store. Thus was created the Wallace Building at 415-417 State Street. Among the attractions of the expanded Wallace's in 1911 were elevators to take you to the upper floors. It was said that "the long skirted, tight-waisted lady clerks of the day seemed thrilled to greet new and old customers."

An advertisement in October 8, 1919, offered satin blouses at $6.98, trimmed hats for dress wear starting at $7.98, and linoleum from $1.69-$3.50 per square yard. In 1925, Wallace's declared as their standard "Always Reliable" (meaning, no seconds or irregular merchandise). By 1941, they boasted "you can dress the family better for less at Wallace's." As suburbanization began to take its toll on downtown Schenectady, Wallace's reached out by declaring itself "The Shopping Center of the Mohawk Valley."

|

| A modern facade was built in the 1950s, obscuring the classic Wallace Building. This photo shows the start of demolition, with the dismantling of the store's awning, in December 1977. |

Further modernization occurred in the 1950s, as three escalators capable of carrying 5,000 people per hour were added. A new, modern facade was also constructed. The 1960s saw the decline of downtown shopping throughout the country, and Schenectady was not immune. Wallace's closed its doors in 1973. The building's facade was demolished in 1977, restoring the classic look for the building. Today, you can find a CVS Pharmacy at the department store's former site.

|

| This 1981 State Street scene shows a number of businesses, including the CVS Pharmacy located in the former Wallace Building. Image from Grems-Doolittle Library Photograph Collection. |

Thursday, December 4, 2014

The Mystery of the Teddy Bear

|

| The cartoon that led to the origin of the teddy bear. |

This blog entry is written by SCHS Assistant Curator Kaitlin Morton-Bentley.

The teddy bear is one of the most beloved toys all around the world, both with children and with adults. Some teddy bears are made to be cuddled and loved, while some designer teddy bears are created to be admired from afar. This familiar object has a surprisingly contentious beginning. The name “teddy bear” comes from a story about Teddy Roosevelt on a bear hunt in 1902 and the first teddy bear was invented the same year. The details of these events, however, are still a bit mysterious.

President Roosevelt traveled to Mississippi to settle a boundary dispute with Louisiana. During a break in negotiations, he was invited to go on a special hunting expedition organized by local sportsmen on the Mississippi Delta. Roosevelt was eager to shoot a bear during the hunt but no bears could be found. The organizers of the hunt finally used their dogs to chase down a bear and tied him to a tree for the President to shoot.

All sources agree that Roosevelt refused to shoot the bear. What happened after, however, is debatable. Some sources say he refused because it was a very young bear and he did not want to take the life of a defenseless cub, and so he set the bear free. Other sources reported that the bear was quite old, and Roosevelt did not feel the hunt was fair. He then ordered the bear killed by a knife and skinned. Roosevelt’s decision to spare the life of a bear became famous when it was recreated in a cartoon by Clifford K. Berryman for the Washington Evening Star entitled “Drawing the Line in Mississippi.” Interestingly, early versions of the cartoon show a much larger and older bear, with later cartoons portraying the bear as younger and friendlier. It is this later version that has become famous for inspiring the birth of the teddy bear.

Soon after the publication of the cartoon, stuffed toy bears called “Teddy’s Bears” began appearing in stores. The creation of the first teddy bear, however, is questionable. Inventors from both the United States and Germany claim to have originated the teddy bear at the same time.

In the United States, Morris Michtom and his wife Rose owned a small candy store in Brooklyn. Inspired by Berryman’s cartoon of Roosevelt and the bear, Rose made a toy bear out of brown plush and stuffing with movable arms and legs. She placed the bear in the store window next to a copy of the cartoon and called the bear “Teddy’s Bear.” The bear quickly sold, and soon they had orders for a dozen more. From this success Morris and Rose formed the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company in 1907, a toy company that lives on today as part of Mattel.

Across the Atlantic in Giengen, Germany, Margarete Steiff had been making and selling stuffed animals for decades before she created her first teddy bear in 1902. Confined to a wheelchair at a young age by polio, she had become an accomplished seamstress and by 1880 established her own company that sold felt elephants, monkeys, horses, camels, pigs, mice, cats, and dogs. After observing brown bears in the Zoological Gardens in Stuttgart, her eldest nephew, Richard Steiff, suggested that she try making a toy bear with movable head and limbs. Margarete was skeptical at first, but when an American toy buyer from George Borgfeldt & Co. ordered 3,000 bears at the 1903 Leipzig Toy Fair, she was convinced of the potential of the stuffed bear. The Margarete Steiff brand quickly grew into an international leader in teddy bear production that continues to produce a vast array of teddy bears and other stuffed animals for children and collectors alike. The Steiff Company maintains today that they created the teddy bear first.

In spite of the mysterious details surrounding Roosevelt’s bear hunt and the origins of the stuffed bear, the teddy bear only continues to gain in popularity worldwide. For play, comfort, or collecting, the teddy bear is like no other.

You can learn more about teddy bears and see some special bears on display by visiting our exhibit, The Teddy Bear: Celebrating the Bears in Our Lives. The exhibit is on display during the Festival of Trees through December 14, 2014. Admission to the Festival of Trees is $5.00 for adults and $2.00 for children ages 5-12. Children under 5 years of age are admitted free. For more information about the exhibit, or about the Festival of Trees, please contact Assistant Curator Kaitlin Morton-Bentley or call 518-374-0263, option 4.

|

| Image from last year's Festival of Trees. The Festival is held annually as a joint fundraiser for the Schenectady County Historical Society and the YWCA of Northeastern New York. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)