This post was written by Elijahjison Powell, Sankofa Youth Collective Ambassador

Not that long ago African Americans did not have the same safety as others traveling this country. There was not GPS or Google Maps to help navigate or tell them about the places they were going. They did however have something called “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” a travel guide for African Americans to use that informed them about everything they needed to know about their destination and the best way to get there. From the Black-friendly businesses to people who could help you around town to the gas stations that would serve you on the way there. We looked through the New York Public Library’s digital collection of Green Books for places related to Schenectady. There were about five people listed in the Green Book under Schenectady County but unfortunately, we were only able to find further information on three.

|

| 1947 Green Book Cover |

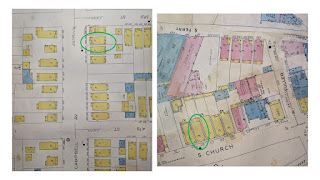

One couple, Rose and Charles Rhinehart, who stayed at 125 Church Street was marked in the Green Book as a “tourist home,” people in the town that were friendly toward Blacks and could help them around town and get settled, or would be nice enough to open their doors to tourists. The 1915 New York Census shows they did just that. 38-year-old Charles and 29-year-old Rose with their 11-year-old son Paul opened their home to a 20-year-old lodger named Thursten Taster.

Another Schenectady resident who lived up to the reputation in the Green Book was Ernest L Claiborn. The 1930 New York state census shows him living at 1808 Campbell Ave with a number of people: his 39-year-old wife Alberta Claiborne, his 20-year-old niece Mary C Williams, his 24-year-old nephew James Williams, and his 50-year-old brother-in-law Thomas Burrus. On top of his big family he let Shirley Jones board at his house and may have gotten her a job. Ancestory.com shows Ernest as head porter at the Hotel Van Curler (now known as Ernst Hall or SCCC; the city of Schenectady bought the building at an open auction for $700,000 and converted the hotel to a college). Shirley’s occupation is documented as a porter in the hotel industry so it is possible Ernest could have gotten a job for her working with him.

|

| 1948 Sanborn Maps of 1808 Campbell Ave. and 125 Church St. |

Another location in the Green Book was the Clefton Hotel, a popular spot within the Schenectady Black community. The hotel was originally operated by Sylvestor Thomas. Around 1945, McDonald Lewis, a Black entrepreneur, purchased the property and renamed it the Lewis Hotel. The hotel’s address was 516 Broadway, an area where most of the local Black community lived. Near the hotel was Detroy’s Chicken Shack, a popular Black-owned restaurant (owned by McDonald’s brother) that featured Black entertainers, music, dancing, and food. As the locals would say, ‘’Good times were had at the Chicken Shack and it’s a jumping place.” The hotel frequently hosted players from the Mohawk Giants, an all-Black Schenectady baseball team. While the Lewis brothers’ personal lives included some troubling episodes, their businesses contributed a positive impact on Schenectady’s Black community.

| |

| 1948 Sanborn map of 516 Broadway |

Victor Hugo Green, New York City postal worker, started the Green Book in 1936 with the sole purpose to help African Americans avoid humiliation and danger. With each update to the book, they covered more and more areas, eventually covering all of the United States and some international locations. The last Green Book was published in 1967, renamed “The Travelers Green Book 67 International Edition: For Vacation without Aggravation.” It was the last one published after the passing of The Civil Rights Act of 1964 making segregation illegal in public places, hence making the travel guide obsolete.

_in_1956.png) |

| Victor Hugo Green in 1956. Photo from |