This post was written by library volunteer Lola Sheeran.

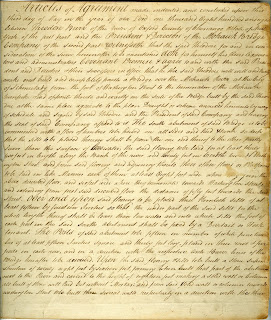

The Burr Bridge, now replaced with the Western Gateway Bridge, first came to fruition in summer of 1804. During its existence, it was known by many different names including the Covered Bridge, Toll Bridge, and the Mohawk River Bridge. There was a lot of demand for a bridge connecting Schenectady and Scotia since people relied on ferries to get across the Mohawk River. Soon after construction on the bridge began, it became clear that the first design of the bridge wouldn’t work. The company and Burr [MT1]went back to redesign it, and finally in 1806, it was proposed there would be a permanent wooden bridge connecting Schenectady and Scotia. The bridge would be designed by Theodore Burr – bridge architect and cousin of Aaron Burr, former Vice President and the man who fatally shot Alexander Hamilton in a duel. On May 13, 1808, Theodore Burr made an agreement with the Mohawk Bridge Company, which described the way the bridge will be built down to the materials and where they will be placed.

The original agreement between Theodore Burr and the Mohawk Bridge Company outlining the specifications of the bridge including price, materials, and obligations toward the bridge.

While Theodore Burr designed the bridge, it was actually built by a man named David Hearsay. He took up a permanent residence next to the bridge so he could keep an eye on it. Another notable man associated with the bridge was Christopher Beekman, but people in Schenectady knew him as “Uncle Stoeffel.” Uncle Stoeffel was a German man whom lived in an old toll-house and was a toll collector for the bridge for 50 years. He also kept an eye on the bridge, and kept it clean and orderly for people crossing the river. According to legend, Uncle Stoeffel was also the owner of a “remarkably well-educated cat [that was] his companion.” Hearsay and Uncle Stoeffel were close friends for 50 years, but they frequently bickered about Uncle Stoeffel’s tobacco use because Hearsay was a devout Episcopalian and hated tobacco. These two men, both living next to the bridge they dedicated their lives to, acted as guardians of the bridge until they both passed away.

According to Larry Hart, in an article for the Daily Gazette, “the bridge was an engineering marvel of its day.” Burr was the first person to attempt a suspension bridge of this kind, and “it was said to be unsurpassed in beauty and solidarity by any structure in America.” The Century Illustrated Magazine stated, “there was only one other [bridge] just like it in all the country,” and the Burr Bridge was so immense it was said to have used wood from Noah’s Ark. After Burr passed away in 1822, the structure was sold to a private group and it was not maintained the way it was supposed to be. The group allowed the bridge to deteriorate and rot until it became too dangerous to cross. According to the magazine “Covered Bridge Topics,” the bridge was left to deteriorate due to weather and time. Sections of the pier began to sag and the company that owned the bridge added additional piers in 1835.

|

| The Burr Bridge from 1872 when the trial about the safety of the bridge was taking place. This photo shows the way the bridge was sagging and deteriorating. |

As the bridge continued to deteriorate due to weather and lack of maintenance, public opinion of the bridge began to change. According to the Schenectady Union Star, “there were not many who mourned the removal of the old covered bridge,” because the condition was becoming dangerous. One example of weather affecting the bridge came from the Schenectady Reflector in 1857. There were reports of floating ice hitting the bridge and causing damage to some of the arch timbers. It caused pieces of the bridge to break off and float along the river. It was no longer seen as a marvel like Larry Hart described. Instead, it was beginning to lean and become crooked over the years. It was impossible to see the other side of the bridge when standing at the entrance because of how much the bridge had shifted. The bridge was also impossibly dark because it was covered and only lit with torches attached to the walls. The planks made loud creaking noises every time people went across.

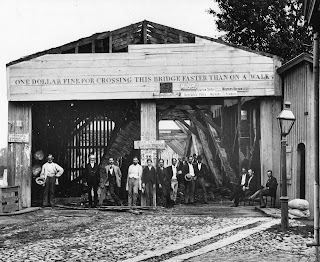

The entrance for the bridge as it was being dismantled in 1874. The writing at the top of the bridge references the prices for the toll.

The state of the bridge caused so much concern amongst the people of Schenectady and Scotia that the state of New York decided to sue the Mohawk Bridge Company in 1872, alleging that the bridge was a public nuisance and the company had failed to uphold its contractual obligations to maintain it. Along with that, the suit claimed the company didn’t keep the toll booth running consistently which was also part of their original agreement for this bridge. Austin A. Yates was the district attorney for this case while E.W. Paige was the defendant’s attorney.

Witnesses for the defendant who lived in Glenville and Schenectady believed there was nothing wrong with the bridge. They testified the bridge had been there their whole lives, and it leaned just as much as it did they first time they saw it, so there’s no reason it should be condemned now. Witnesses for the state described the bridge as leaning and the wood as rotten; one of the witnesses even brought in pieces of the rotten wood from the bridge to show the jury. Testimony from bridge builders and engineers agreed the bridge was unsafe; it could potentially be used for local traffic, but putting too much weight on the bridge could be risky.

One notable story about the bridge was the time a circus came to town. There were elephants and hippopotamuses that were to cross the bridge. A witness for the defendant, Harmannus Van Epps, a toll collector for the bridge for many years, claimed the hippopotamus made it across the bridge with no hitches – clearly a testament to the bridge’s strength. When questioned about the elephants, he claimed, “I recollect the elephant that swam the river but he did it from choice,” not because he was too big to fit on the bridge. The jury found the Mohawk Bridge Company guilty of letting the bridge deteriorate to this state. The trial and verdict led to the bridge being dismantled soon after in 1874. A new bridge was built in 1874 made out of iron which lasted until 1939. Construction began in 1922 on the concrete bridge, the Western Gateway Bridge, which is still standing today.

Map showing where the old bridge was in relation to where the new bridge. The change in location was meant to accommodate the amount of traffic expected to cross the bridge.

Bibliography:

“Burr Bridge was an Engineering Marvel of its Day” by Larry Hart

“Covered Bridge Topics – Official Magazine for the National Society for the Preservation of Covered Bridges”

“First Mohawk Bridge had many names but served public well,” by Larry Hart

“History of the Mohawk Valley: Gateway to the West 1614-1925”

“How the Great Western Gateway Will Remove Danger and Traffic Congestion in Schenectady,” 1919.

Chapter 83: Mohawk River Bridges” from Schenectady Digital History Archive

History of Schenectady County, NY by Hon. Austin A. Yates

Schenectady Reflector February 13, 1857

“Tales of Old Dorp” by Larry Hart

The Century Illustrated Magazine vol. 12, 1876

The People of NY vs. Mohawk Bridge Company court case