Over at the Grems-Doolittle Library, we love everything about October. What’s not to love? There’s peak leaf peeping, sweater weather, apple everything, and of course, National American Archives Month! This October, the Grems-Doolittle Library staff and volunteers were busy preparing for our new shelving system and looking forward to many more years of collecting the documentary heritage of the county once the system is in place! However, many librarians and archivists across the country celebrated National American Archives by pulling back the curtain and revealing some of the behind-the-scenes work that goes into making archival materials available and accessible for current researchers and future generations of researchers. While I'm little late to the party, I wanted to join in the spirit by talking a little about what happens when people donate their personal papers, family archives, or organizational records to the Grems-Doolittle Library.

The first step in any archival donation is reviewing the materials with the donor. At SCHS, we use our Donation Questionnaire and Donation Guidelines to get the conversation started. For example, I need to know how much material is currently in the possible donation, what types of materials are included (e.g. documents, photos, framed items), how the material is currently stored or organized, and how the material came to be in the donor’s possession. I’ll ask follow-up questions to figure out how the material relates to Schenectady history, the materials we already have in the collection, and our ability to care for the materials long-term. Our Collection Development Plan informs and guides the decisions we make about what donations to accept. If I decide to accept the donation and add the materials to our collection, the donor needs to sign a deed of gift and we’ll then need to set up a date and process to transfer the materials.

When the donated collection arrives, I evaluate it for preservation/intellectual property/privacy concerns and create a processing plan. The processing plan explains what work needs to be done so the collection can be safely stored, properly documented, and easily accessed by future researchers. It includes the decisions that I make as the SCHS archivist and my rationale so that future archivists and curators can build on those choices or use the collection for exhibits and special projects. The library's highly skilled volunteers help with this processing, but we may also engage a library science/archives/history intern, depending on the season and the amount of work involved.

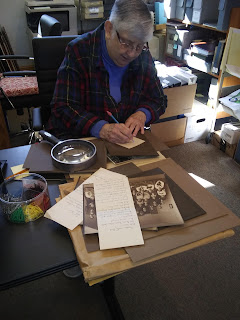

|

| Carol, a retired librarian and one of the library's longest-serving volunteers, works on researching and describing materials in a donated collection. |

For every accepted donation, we catalog the collection in our online catalog. The materials often need to be arranged for best preservation and ease of use by future researchers. Sometimes this means maintaining the original order used by the collection creator (scrapbooks, for example), but it often means creating a logical order out of something that seems like chaos. Information provided by the donor can be helpful in determining the arrangement, especially if there are any privacy or intellectual property concerns. For example, a collection of photographs could be organized by the contents of the photos (e.g. all of the portraits together) or by photographer if there is more than one. If the intellectual property is held by the photographer and not the donor, it often makes more sense to organize the photos by photographer so that we can more easily answer questions about copyright, digitization, and duplication. Finally, we describe the collection in a finding aid. Finding aids provide information about the collection to help researchers identify relevant materials and navigate access and use of the collection. They are usually more detailed than the entries in the online catalog, and they follow a format that most other archival repositories use. In addition to our online catalog, researchers can find our collections using EmpireADC, a state-wide finding aid discovery platform.

After the initial cataloging, we transfer the materials into archival/preservation housing such as acid-neutral folders, photo sleeves, and specialized archival boxes. While we work on processing the collection, the library volunteers and I implement necessary preservation solutions such as creating digital copies of at-risk media like VHS tapes, copying newsprint materials, isolating materials that may have mold or pest damage, flattening rolled or folded materials, and stabilizing oversized/fragile/damaged materials. Once the collection is processed and stabilized, the materials are stored with the other archival collections in our climate controlled vault. We regularly monitor the area for preservation concerns such as changes in heat/humidity or the presence of damaging agents such as pests and water.

Researchers who want to view or use the collection can make appointments in the library. The finding aid will note if any materials are restricted due to privacy, intellectual property, or preservation concerns. As the collection is used, we may need to update the finding aid and catalog record with any new additions to the collection from the donor or new information that comes from researchers using the collection in the future. Materials in the collection that appear to have significant research value (e.g. something unique to Schenectady's history or a person with a regional/national/international impact/reputation) and clear intellectual property rights will be evaluated for potential digitization and future blog posts or other promotional activities. We add digitized collections to our NY Heritage site.

|

| Part of a newly donated collection of slides from the Annie Schaffer Senior Center Photography Club, ready to be processed. |

No comments:

Post a Comment